When Colson Whitehead or Jesmyn Ward write about Black experience, it’s what they’re bringing to the table. Like many writers, I’m wearing this mantle, I have to represent my people.

How did you think about how much this book ought to intersect with the real-world politics of its time? And he mentions other words like that: redneck, moonshiners … deplorables. I’m thinking of that bit when he’s talking about the word hillbilly, how it’s been reclaimed by some people as a mark of defiance. The book isn’t overtly political, but every now and then Demon reveals he’s paying attention. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

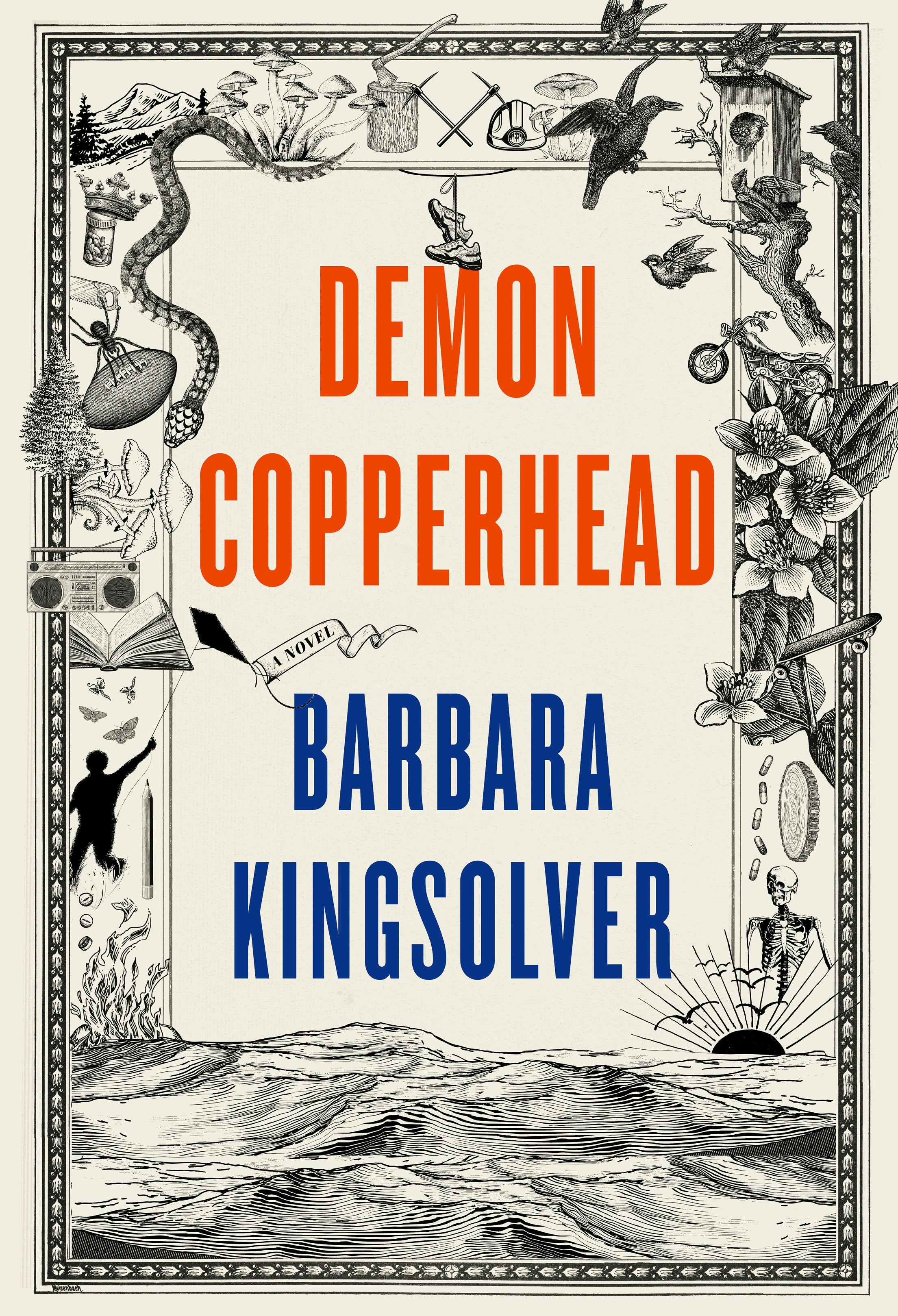

Vance portrays Appalachia, about leaving home and coming back, and about the forgotten history of Appalachian progressivism. It’s a propulsive reading experience, energetic and funny while still conveying Kingsolver’s fury at the institutions that have let her community down. As the title suggests, it’s a backwoods twist on Dickens’ David Copperfield, starting from the opening sentence, “First, I got myself born.” Demon, né Damon, is a chatty, likeable orphan whose life gets caught up in the structural poverty and opioid epidemic that plagues rural America. Kingsolver’s new novel, Demon Copperhead, takes her back to Appalachia, where the author was raised and where, after decades away, she once again lives, on a farm in southwestern Virginia. It’s easy to dismiss her novels as middlebrow, but I’ve found the best of her work angry, engaged with politics, and alive to the natural world in ways that have only felt more relevant as tastes in fiction have evolved. Barbara Kingsolver has been writing about issues of social justice for decades, starting with her first novel, 1988’s The Bean Trees, set against the backdrop of immigrant life in Arizona.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)